In ancient Greece, “In order to achieve adult female status a woman has to become an object as much as a subject; she has to accept and embrace her objectification by the dominant discourses of her culture and internalize a construction of her identity.”[1]

Maenads have often been discarded as flippant characters within Greek mythology, bearing little significance in iconography of ancient Greek vase painting. Few have focused on their importance as individual characters within the narrative of the Dionysian cult. Furthermore, the role of voyeurism in both the depiction and consumption of maenadic figures has long gone unchecked. In order to fully understand the female citizen in ancient Greece, it is crucial to ask the question: In what ways are maenads depicted as agents and active figures and/or non-agents and passive figures? Why and how are these figures objectified? As Barbara Goff states, in the context of ancient Greece a woman must come to terms with her situation as ‘object’ within her own culture. What follows is a close examination of the mythical depictions of maenads and how they proved to represent larger social constructions of women and their relationship to men by embodying both socially normalized ideals of femininity and an oppositional inversion of such stereotypes.

The word “maenad” has been translated to mean, “raving woman” and is often aligned with religious fanaticism. The 6th century poet Anakreon referred to maenads as ‘the hip-swaying Bassarids’[2], referencing their characteristic dances of possession and madness. According to Eva Keuls, “The Maenads, in their most unrestrained behavior, act like persons in an ecstatic trance: they throw back their heads; raise their arms in wild gestures; and maul animals, mostly young ones, in the cruelest fashion and brandish their severed limbs. They let snakes entwine in their arms and they ululate and make a noise with clappers.”[3] They often carry a thyrsos, a fennel stalk topped by a pinecone, as the characteristic wand (or some would say, spear) of the Dionysian cult.

The depiction of such figures in vase painting took off in the earlier part of the 5th c BCE, during an “era of the sharpest sexual polarization in Athens.”[4] It is this critical period in the analysis of sexuality that makes the vase paintings of maenads particularly interesting to study. Generally, these vases were created by and for men. They were often used in the symposia setting, surrounded by ample drink and the pleasures of male privilege. For as female subjects of the male painter’s imagination and brush, depictions of such women were often open to voyeurism and possession. However, the definition of voyeurism in ancient Greece was much different than we would define it today. It is crucial to this study that one recognizes how ancient Greeks defined voyeurism, and how that may have influenced the depiction of female bodies—specifically maenads.

The modern definition, according to Justina Gregory, pertains to “sexual aberrations […] and the state of mind of the voyeur;” one that sees what should not be seen. This entails both physical and mental violations of the viewer upon the viewed. However the Ancient definition “emphasizes the act itself and its inevitably evil results.”[5] It is not the actual vision of the forbidden, but the violation of a sacred act that is distinctly private and unwelcome to view

ers. It is the actual physical manifestation of mentally conceived transgressions that constitutes voyeurism in ancient terms.

An essential aspect of voyeurism to be analyzed further in this paper is the notion of possession. A voyeur takes possession of the figure, transforming it into an object rather than subject. Andrew Stewart posits, “My capitulation to this shame-engendering gaze deprives my body of its primacy as the agency of my actions, turning it instead into an object of the Other’s scrutiny.”[6] Therefore the depictions of maenads on vases are nearly all inherently voyeuristic—such bodies are, in most instances, not their own subjects but rather objects of desire and seen as symbolic manifestations of unrestrained sexuality. As such, there exist two dichotomous categories that I plan to investigate within my paper: the situating of maenads as active or passive and as agents or non-agents. Through the lens of a voyeur, one can distinguish varying amounts of agency and activity (or lack thereof) throughout vase paintings of maenads.

The depictions of maenads can be broken down into three categories:

- Maenads as objects of possession and lacking agency,

- Maenads solely as mentally (not physically) possessed while still lacking agency due to their raving state, and finally,

- Maenads as capable of actually possessing another, existing independently from the male gaze and grasp while exhibiting a small, yet limited amount of agency.

All three of these categories inherently call into question ideas of possession and action in relation to the gaze of the both the real and the depicted, painted viewers.

As seen in this first grouping of figures, many maenads were depicted as prisoners of another’s desire—as an object of possession and completely lacking agency. Such images often entail attacks of molestation and aggression, of being unwillingly possessed both visually and physically.

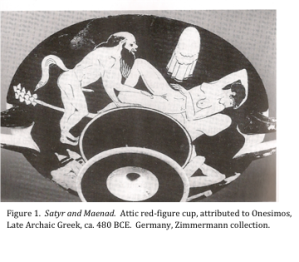

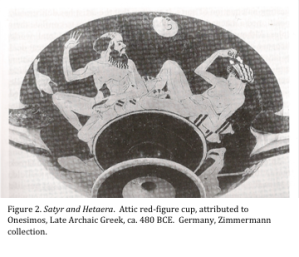

Figures 1 and 2 are found on the reverse sides of a kylix cup from 480 BCE. The first is identifiably a maenad because of the thyrsos lying near by. The aroused satyr approaches her while she sleeps, unaware of his presence indicated by the downturn of her head and the limp appearance of her limbs. On the other side, a satyr and a female prostitute are depicted facing each other, both aware and prepared for consensual sexual interaction. “The woman’s intentional nudity and the directress with which she meets the satyr’s gaze indicate that she is a hetaera.”[7] Compared to maenads, hetaera would have sex with satyrs for money while maenads were victims of molestation. The difference between the two can be defined in terms of possession. The hetaera is both willingly solicited and possessed while the maenad is both preyed upon and possessed by both the god Dionysos and bestial satyrs.

The interplay between these two scenes suggests how the satyr is untamed and wild within the realm of mythology, amongst the maenads. However, the depiction of the same satyr in the real world symposium setting renders him less powerful and capable of forcefully possessing the woman: “the satyr is no longer depicted as aggressive and ithyphallic, but in a sense been ‘tamed’.”[8] This speaks to the fact that in most depictions, maenads often had no power over satyrs; nearly no ability to stop their advances, only further empowering the beasts to take advantage of them.

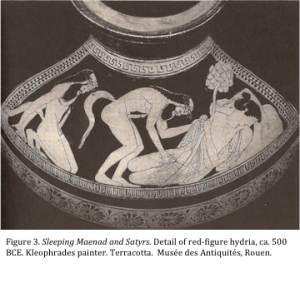

In another depiction of the molestation of a maenad, one becomes aware of the presence of the real viewer. Figure 3 shows a sleeping maenad whose garment is being lifted by an ithyphallic satyr, groping her thigh. Interestingly, the maenad is situated in such a way that she is exposed to the viewer (of the vase) as well as to the satyr. This indicates the hand of the male painter in offering the maenad’s body to the gaze of the viewer, as well as the gaze and touch of the satyr. Here is the epitome of possession and voyeurism in the depiction of maenads. Not only is the viewer privy and welcome to the molestation of the figure, but also the repeated depiction of such a scene (Figures 1 and 3) suggests that maenads generally lacked agency and subjectivity—instead, in many similar cases, maenads are passive objects of possession.

The second category of representation is the depiction of a state of mental (though not physical) possession. In these cases, maenads are depicted in a state of ecstasy and uncontrollable madness, still lacking agency in that they cannot control their actions. However, compared to the first category of depictions, these figures are not the victims or objects of another, but rather in a drunken stupor, an orgiastic trance (see figure 4). In a post to the blog What Do I Know… by Kenneth Hope on May 25, 2007 he suggests, “for her, time and space have altered, or gone completely missing, vanished with whatever happened to her consciousness.”[9] She embodies ecstasy and energy, convulsing in dance, crying and shouting in the forest at night, tearing all those in her path to pieces. Kallistratos writes of Skapos’ sculptural depiction of a raving maenad, she “seemed to shout the Bacchic cry, a more piercing symbol of her madness.”

Essential to this state of madness was the presence of the cult god Dionysus, known as “he who drives women mad”. It was said that only women lost control of themselves in such a state; men merely acted out their roles. As such, the act of mental possession is voyeuristic in that the male orchestrates both the gaze and control over her body. The male gaze is privileged to the unrestrained, uninhibited actions of the maenads as both possessor and viewer.

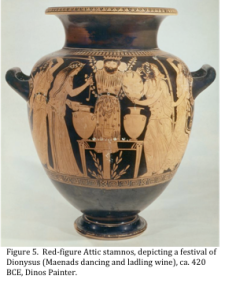

Figure 4 shows a collective group of ecstatic maenads convulsing and contorting in a typical frenzied state of possession. Depictions of this kind almost never feature additional characters, especially male figures, for their raving state was considered an intrinsic outlet of being a woman. For men, a comparable state was achieved through plentiful drink and celebration in the symposium setting. However, as Barbara Goff suggests: maenads (as women) are not in any way “a symbolic part of the human symposium in order to experience the ecstasy of the god.”[10] More simply put, women were transformed into the frenzied state in mythology, completely losing all faculties of modesty and self-awareness. This, Goff explains, is why maenads are rarely seen frontally, facing and interacting directly with the viewer compared to depictions of satyrs and the god Dionysos. Since male figures were always ‘playing’ a role, they did not experience the same ecstatic trance, indicating that never lost their agency and sense of self. This simple inhibition—that maenads were rarely depicted actively looking out at the viewer—speaks largely to the sexual politics of both Greek life and Art.

Full frontal faces in art mostly belong to the realm of Dionysus, god of abnormal states, and powerful vision. Figure 5 depicts a Dionysian festival in which the god is depicted frontally while the maenads, dancing and ladling wine to honor him, are depicted (as always) in profile. Being shown frontally in Greek iconography signifies one that can “take possession of another’s wits,”[11] therefore acting as an active agent of possession.

The inability to be depicted frontally distinguishes those who are possessed by the god: “his apostles: drunkards, satyrs, maenads, ecstatics, actors, musicians, and pipers,” from those who actively possess others. Yet among these, maenads are the only figures who are unable to possess others in return. In Plato’s Timaeus from 360 BCE he demonstrates how being possessed and the ability to possess are linked, however, maenads are poignantly left out of his description of those capable of this duplicitous existence. Instead, maenads are only capable of being possessed; having no agency to actively possess another, to bring another into the same frenzied state of possession brought on by the god.

Eric Csapo offers the explanation that possession was believed to be an inherently male quality, associated with male ‘seed’: “it is the nature of male genitals to be disobedient and self-willed and, like an animal which will not listen to reason, out of a mad lust it attempts to take possession of everything.”[12] This may explain the belief that females, lacking the phallic-specific qualities of self-will and possession, were only capable of being possessed themselves. However, there exist multiple narratives in which maenads exhibit minor forms of agency by actively attacking other whilst in this ecstatic, raving state.

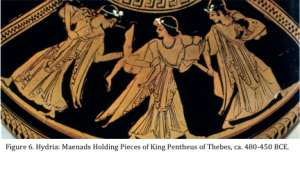

Myths expressing female aggression and hostility against males were common in ancient Greece. It was said that raving women dismembered Dionysos himself as well as the legendary cult figure Orpheus. Another myth circulated claiming that the widows of a destroyed Athenian fleet grabbed the messenger that had brought the unfortunate news and stabbed him with to death in a frenzied state of rage. Figure 6 exemplifies the third and final category in the depiction of maenads—situating them as actively assaulting and possessing others, showing a small limited amount of agency.

This vase depicts a scene from Euripides’ Bacchae, where King Pentheus of Thebes being torn apart by two maenads. The King violates the sacred privacy of the cult, saying he would pay anything to witness the wild debauchery of the Maenads. In this way, he was acting exactly akin to both the ancient and modern definition of the term ‘voyeur’. According to Justina Gregory: “the essential point [is that] the man ‘sees what he should not see’, [it not as if] he is disturbed or deviant, but that he has violated some prohibition” by looking upon the private gathering and practices of the maenads.[13] This implies that both the male viewer of the vase and the male depicted are violating the privacy of the maenadic cult. Furthermore, the maenads themselves deliver his punishment by tearing him limb from limb in their fit of rage. This example shows the very slight amount of agency given to maenads as they are allowed to punish the transgressor. However, the problematic lack of politicization of women in ancient Greece immediately positioned them as inferior to men. How then, were maenads able to actively assault and kill their superiors if a woman was essentially powerless in the polis?[14]

In ancient Greece, a woman was often defined as an “inferior or unfinished male.”[15] This speaks to the immediate hierarchization of female bodies, seeming to belong only to the private domestic sphere. However, it is here that one finds another important aspect of maenadism: the subversion of the socially acceptable role of “woman” for the wild prowess of a maenad. Bruce S. Thornton calls attention to the inversion of control over the female body when “Pentheus’ god-intoxicated mother Agave […] brags that she ‘quit the loom and the shuttle,’ liberated herself to become a hunter, shedding her culturally imposed role.”[16] In this way, maenads symbolized women free from the constraints of the home, shown in the wilderness, wild, erotic, untamed.

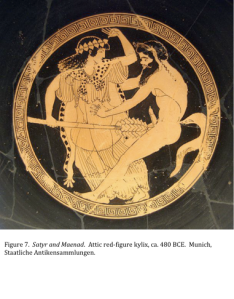

Within the depiction of maenads, there exist a few instances in which symbolism alone speaks to a certain amount of agency. Figure 7 shows an angry maenad brandishing a thyrsos in defense against an ithyphallic satyr. As previously established, the satyrs’ main purpose in their interaction with maenads is to take advantage of their ecstatic state through molestation. However, according to Eva C. Keuls, maenads were shown to “attack them in defense,” using the thyrsos as a weapon.[17] Though function and symbolism of the thyrsos is widely debated, some believe it to be a phallic symbol carried to combat the bestial, untamed desires of the male phallus. As such, this vase painting shows a maenad actively defending herself, embodying female action and agency, by retaliating against the advances of the ill-intentioned satyr.

Reading Athenian vase paintings exposes the Greeks’ attitudes towards woman as Other, and in particular toward the untamed women of ancient Athens. Women were marginalized in Greek society as tame, docile, and domestically bound. Maenads critically broke these stereotypes as wilderness dwellers of uninhibited pleasures and passions. As Jenifer Neils suggests, Maenads were characteristically Others within Other; further marginalized because of their direct opposition to the appropriate and conventional role of ‘woman’ in ancient Greece—“an inversion of polis values.”[18]

In comparing three categories of the depiction of maenads, one can see how they were both active and passive figures as well as agents and non-agents depending on the circumstance. The production and consumption of such figures indicates larger social phenomena that existed in Greece regarding women and their subservient role to men. Specifically in the depiction of maenads, one can see both the proliferated objectification of woman and the inversion of such a stereotyped role. It is through the depiction of maenads that another definition of what it meant to be a woman was created—introducing aspects of uninhibited rage, anger, and power embodied in the feminine form.

[1] Barbara Goff, Citizen Bacchae: Women’s Ritual Practice in Ancient Greece (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2004), 78.

[2] Jenifer Neils, “Other Within the Other: An Intimate Look at Hetairai and Maenads,” in Not the Classical Ideal: Athens and the Construction of the Other in Greek Art, ed. Beth Cohen (Leiden: Brill, 2000), 219.

[3] Eva C. Keuls, The Reign of the Phallus: Sexual Politics in Ancient Athens (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1985), 360.

[4] Keuls, The Reign of the Phallus, 357.

[5] Justina Gregory, “Some Aspects of Seeing in Euripides’ ‘Bacchae’,” Greece & Rome 32.1 (1985): 24.

[6] Andrew Stewart, Art, Desire, and the Body in Ancient Greece (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997), 13.

[7] Neils, “Other Within the Other,” 204.

[8] Neils, “Other Within the Other,” 205.

[9] Kenneth Hope, March 25, 2007, “Maenad, Skopas,” How Do I Know…, http://idliketocallyourattentionto.blogspot.com/2007/05/maenad-skopas.html

[10] Goff, Citizen Bacchae, 270.

[11] Eric Csapo, “Riding the Phallus for Dionysus: Iconology, Ritual, and Gender-role De/Construction,” Phoenix 51.3 (1997): 257.

[12] Csapo, “Riding the Phallus for Dionysus,” 260.

[13] Gregory, “Euripides’ ‘Bacchae’,” 24.

[14] “superior” meaning those situated hierarchically above women, solely based on gender, not just political or social status.

[15] Stewart, Art, Desire, and the Body, 101.

[16] Bruce S. Thornton, Eros: The Myth of Ancient Greek Sexuality (Boulder: Westview Press, 1997), 75.

[17] Keuls, The Reign of the Phallus, 362.

[18] Neils, “Other Within the Other,” 226.